Morse President, Nate Andrews', interview with Syracuse media focuses on leadership

Know yourself, understand what makes you happy, hold to your moral compass

By Stan LinhorstOriginally published by syracuse.com on Sept. 28, 2014

When a tsunami damaged Japan's Fukushima nuclear power plant in 2011, the cleanup required special equipment. The call went to Morse Manufacturing in

East Syracuse for heavy-duty machines to dispense treatment in radioactive waste water.

When a tsunami damaged Japan's Fukushima nuclear power plant in 2011, the cleanup required special equipment. The call went to Morse Manufacturing in

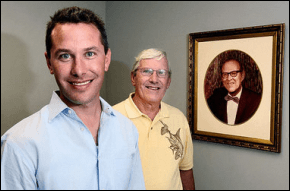

East Syracuse for heavy-duty machines to dispense treatment in radioactive waste water.Nathan Andrews is president of the company, a family-owned maker of specialized drum-handling equipment. A call from the other side of the world is not unusual, and the company thrives on difficult, custom-made products.

J. Mott Morse, a local inventor, founded the company on Syracuse's Dickerson Street in 1923. By the 1940s, Nathan Andrews' grandfather, Ralph Andrews, had focused the company's product line by inventing specialized machinery to handle industrial drums, creating the industrial equipment category of drum handling equipment.

The company manufactures its products in East Syracuse. Two percent of the company's customers are in New York. At least 25 percent are outside the country. A normally modest Andrews can say with soft-spoken confidence: "We are the best company in the world at making specialized drum handling equipment."

Consumers don't buy Morse products, but they buy plenty of products made with Morse equipment. When Estee Lauder or Sherwin-Williams or Pennzoil need special equipment to make huge batches of mascara or mix paint precisely or move around used oil, they use Morse's drum-handling equipment.

Were you in leadership roles growing up?

I had some leadership roles through Scouting, as well as through athletics. I was a leader on swim teams.

I learned a lot through my father. Coming back here and learning from the ground up instilled a lot of those attributes.

Where did you move back from?

I went away to college, the University of Vermont. I moved to Boston after that. I worked for an organization called Young Life for a couple years. I wasn't sure if ministry was in the works for me, so I spent a year at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Boston.

I got through a year of it. The second semester of ancient Koine Greek did me in.

I went to work at a market consulting company, one of those jobs where they take young people and work them to the bone. You're thrown in way over your head and you learn a lot.

We did market research for high-technology products. The first report that I worked on was about a little chip on the inside of your cell phone that determines the battery life you have left.

We studied the entire worldwide market for it, called up all the major suppliers, all the major customers, worked closely with them and project managers and developed a research report. After we became proficient, we sold our consultant services and market research reports.

It was a fantastic experience. I worked there about four years, and I left there as a manager to come back to Syracuse to join the family business.

When I got here, I put on a pair of steel-toed boots and a uniform that said Nate. My dad said, "If you're going to learn this, you've got to learn it from the bottom up." I worked on the shop floor, learning every aspect of the business: Welding, sawing and working side-by-side with pretty much everybody.

A generational handoff can be difficult.

The idea of moving back to work with your father is daunting.

You grow up and there's a father-son relationship. Now you're working together. We had that process of becoming friends as opposed to father-son and becoming co-workers and yet still family members.

My dad had a real challenge going through that process with my grandfather. My grandfather didn't necessarily want to give up control. They had some hard times.

Tell me about leadership attributes your father instilled.

You have to define your own leadership. Leadership has to come out of you. I don't think I can look to my father and say, OK, teach me leadership.

To be a good leader, you have to know yourself very well and you have to know what motivates you. You have to know very closely where your moral compass lies, what boundary lines you set for yourself.

You see how true leaders hold to their moral compass, and they instill that in the employees around them.

What's your leadership style?

It's certainly not a dictatorship. We don't tell people, "You've got to do it this way because I say so."

I lead by moral example. I keep coming back to the morality issue. We want our people to do the right thing.

If a customer calls with a problem, we want to treat them as we would want to be treated as a customer. If you were sitting in their shoes and there was a problem of some kind, you don't blame it on some policy. You don't say no, we can't do that. You reach out and make it work, because that's how you would want to be treated.

Add to it: You have to genuinely care.

The average employee has been with us over 15 years. I know the employees' family, I know their spouses, and I know their children. If you genuinely care about the people, you want to empower them. You want them to develop as individuals and as employees. The company is a success because of its employees.

What tips do you have for somebody new to leading an organization?

You have to know yourself. You have to understand what makes you happy in life, what gives you satisfaction. Is it money? Is it acknowledgment? What is it that makes you tick?

You have to know where your moral boundaries are, where you are willing to go to achieve whatever it is that you desire. I think it really comes down to knowing yourself through and through, so you can stand hard on whatever principles you need to, because at some point you're going to have to. You're going to have to say, "No, I'm standing my ground." You have to be the rock for an organization to lean on.

I'm relatively young -- 39. So I haven't had immense opportunities to teach leadership. But I think you teach leadership in much the same way you learn leadership: By watching others. You can tell true leaders when you meet them. Watching them, seeing how they behave, observing their moral compass empowers you.

What other tips would you have for business success?

You've got to embrace technology. Maybe that's number 1.

You have to stay ahead of the curve whether it's social media, whether it's iPhones, whether it's something else. We bought a new robotic welder last year. Staying up to speed in our production end of things is key.

You have to stay up to speed in the sense of business practices. We've gone to great lengths to pursue and adopt lean manufacturing. It's made immense improvements in reducing our inventory counts and cycles and increasing our throughput times.

You have to surround yourself with trusted advisers who know what you don't know. Like my father, I know drum-handling equipment. I need help regarding banking, regarding insurance, regarding accounting, regarding a lot of other aspects that I need to run this business successfully. You can't know everything about everything.

How do you go about changing an organization to meet new demands and circumstances?

Change is always difficult.

Constant incremental change is part of that process. If an organization continues making incremental changes, making a big change every now and then is a lot more acceptable.

In healthy organizations, there should be incremental change and continuous improvements. You need to get people to rethink processes, how we're doing things, and whether it's the best way.